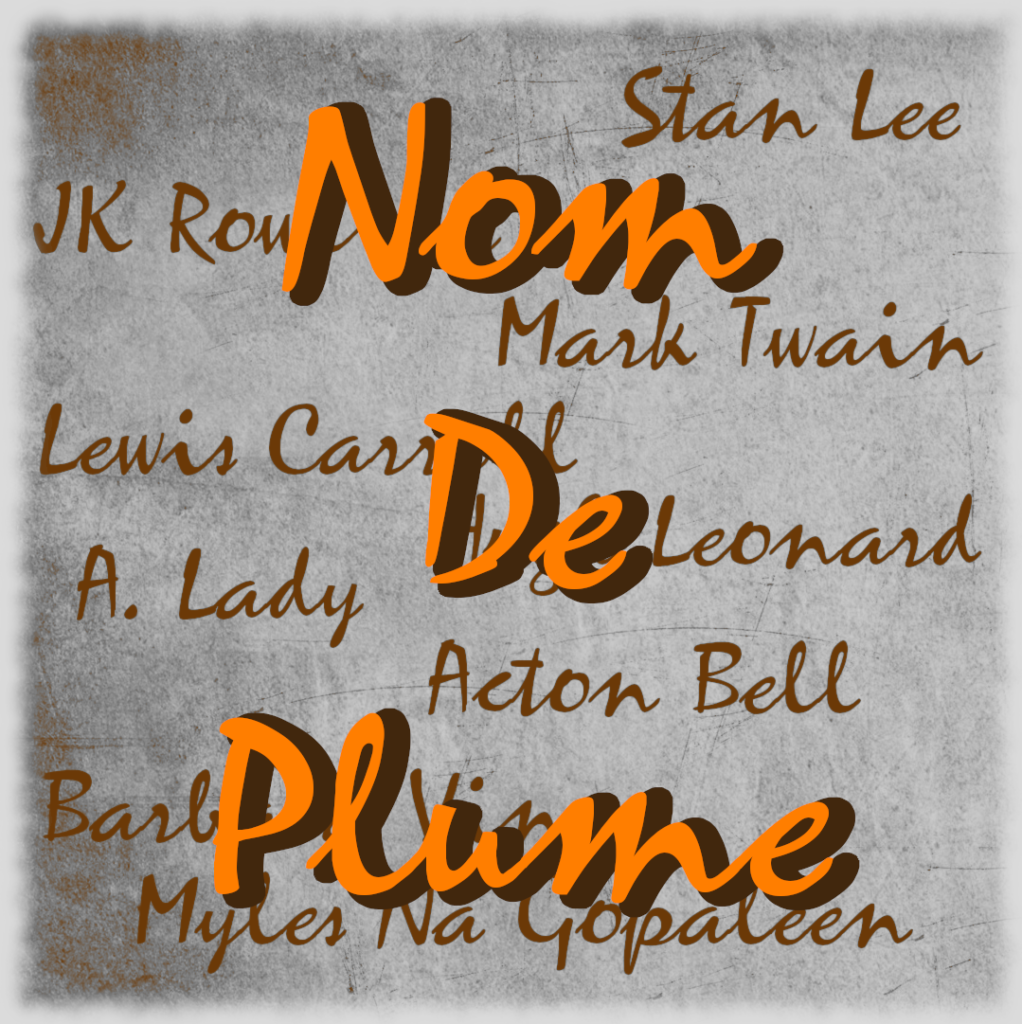

Why, you may well ask, would I even think of using a Nom de Plume? It is not like I am a civil servant who could get themselves, or their government, in trouble by expressing ideas which might be problematic for their political bosses. Hugh Leonard and Flann O’Brien were names chosen to protect the writers from becoming unemployed civil servants. Not that Flann was happy with only one pseudonym, he also wrote under the protective umbrella of Myles Na Gopaleen. One might argue that the name change, not only protected Flann, but also his family. He was a difficult man at the best of times to explain away. Imagine how a maiden aunt might have felt if she became aware of his strange, writing proclivities. Think of the strain she would have taken upon herself, the delicious guilt of being related, no matter how tentatively, to this peculiar genius. Imagine the almost teenage glee of confessing sins on his behalf, to the local parish priest, sins hidden in prose she could never bring herself to read, and which must be all the more suspect for that. After all, if you cannot, for fear of contamination, open one of his books, there must be terrible sins hidden inside. Oh, the shame of it!

His uncontrollable urge, one he indulged, to lock himself in a room and write some of the most extraordinary fiction ever written by an Irish man, would have been seen by many family members as eccentric at best, perverse at worst.

So, there are many a good reason for a Nom de Plume, at least there were, you might argue. There is no need for one now, in these liberal times, you might say, but are you sure of that? Think of the hordes of internet trolls simply waiting to shred to pieces writers they happen to take offence with. While they have every right to be as offended by an author’s work as their grandparents had, the writer should have as much right to her privacy as her grandmother had. Think of all those who had to have a flag of convenience to avoid looming troubles, or to get published at all.

You may not be aware of it, but many writers were continuously at war with the rest of their society. And in a way they still are. Many are on the frontline of the culture wars. These move with the times; today’s liberal is often seen as tomorrow’s conservative. As the times are always in flux, attitudes always changing, the winning side is never clear cut. Many writers are simply part of the clamouring classes as myopic as their peers. But there are always those who see clearly. They will never be the most popular, or the most widely read, because they will present as balanced a view as possible. They will mostly fail, but they will strive heroically first. Fighting in a headwind no one else can see, they should have a Nom de Guerre rather than a Nom de Plume.

Think of that age old tradition of giving newly recruited troops each a war name. Thomas the Brave sounds far better that Tom Smith 1072 and far more intimidating when shouted across the battlefield. Imagine you were christened Alfonse Patrick Mary Brown, where is the blood curdling inspiration in that? But perhaps Alfonse Patrick Mary is a strong lad, and a passingly good archer, why not call him Strong Bow? And as for Dan Murphy (whose sole indication of brain function is his continuous misinterpretation of the word forward to mean retreat?) What shall we call him, after handing him a mop and putting him on permanent latrine duty? Somehow, I suspect he would become Dysentery Dan and would be scarier to friends than foe. Every army has them, no matter what their true name is.

Who, you may wonder used a Nom de Plume in the past? So many, that I could write a doctorate paper on a tiny cross section of them and still leave room for hundreds of scholars to mine this seam of intellectual gold after me. Not that a dead writer has much to say of such small-minded pursuits.

Take Jane Austen, published as A Lady. She was not alone in being A Lady. Bookshop shelves of that era were creaking under the weight of A Lady’s works. Imagine the insult to Jane and all her fellow A Ladies of the time. Think of the biting satire she must have contemplated writing about the publishing industry she was forced to work in. There must have been a ‘Pride and Prejudice Among the Printing Presses of London,’ begging to be written by her.

As for the Bronte sisters. They were so harassed by the male dominance of the writing scene that they were forced to publish under the names of the three alleged brothers, Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.

Samuel Longhorne Clemens, was so weighed down by his name that he could not publish under it. The name is so whimsical and elitist that no one could imagine that it would hide a biting satirical voice, one that resonated with millions, but only after its owner hid behind the name, Mark Twain.

Stephen King also wrote under the name Richard Bachman. In his case he was not hiding the fact that his parents had gone mad at the baptismal font. He was disguising the fact that he was simply too prolific for his publisher to admit to. No writer, they assured him, could be taken seriously if they published more than one book a year. Eventually Richard Bachman died of ‘cancer of the pseudonym.’ What a way to go.

Stan Lee was a pseudonym that became Stanley Martin Lieber’s legal name after he became too successful as Stan Lee to deny his involvement with The Marvelverse he helped create.

There are many reasons for changing your name on the cover of a book. But the main one is about shelf appeal. How many people would buy into a children’s fantasy book by Anne Rice. Maybe, if she had form. But as a new writer… Better to add a couple of initials followed by an extra syllable or two. And thus, J K Rowling was hatched. She was also later published under the name Robert Galbraith, because the expectations of her loyal Harry Potter fans would have been shattered by real world fiction set in an adult world.

It is the real world which concerns me. How would my name look to the eyes of people interested in crime fiction. The readership is mainly female, and they have very fixed expectations about authors. While, in the past, women changed their names to appeal to a general readership, now more men are doing so. For instance, there is a very large, bearded gentleman who only recently stepped out from behind his Nom de Plume. He was a romance novelist who feared terrible sales figures if his readership learned of his sex. Most people however, simply use their initials as the flimsiest of disguises. If that gets past the prejudice of the reader to such an extent that they pick up your book, then it is worth considering.

The question remains, should I wear a public disguise, or not?

Jim Clarken is as good a name as I require in everyday life. But how would it look on a bookshelf, fighting for the attention of a browsing public? Would James look better? How about Seamus? Is the balance right? I could use the name James Thomas, my first two names, but that is sure to be in use by somebody else. Thomas Aquinas could be legitimately used too, don’t ask, it was a baptismal mistake. No one remembers this gluttonous philosopher now, it would raise no eyebrows if, hundreds of years after his death, he broke into the crime market. As for initials, ‘J.T. Clarken,’ has no balance to it. I hate to say it, but I might have to be myself.