By all definitions I am sinister. What a word to be associated with, not even by choice, and without any hellish, hedonistic rewards being showered upon me by some malevolent being who is said to smile on evildoers everywhere.

This adjective, which causes heroes to sharpen their blades and polish their breast plates, is a cross I was born to carry. The word seems to perfectly match its purpose, having a marked sibilance, a snake-like hissing sound, with reptilian connotations. On hearing it, one’s mind immediately thinks Hitchcock and sends a shiver down the spine. The imagination turns black and white. It becomes cluttered with shadows and shower curtains, blades opaquely defined, strings screeching in the foreground, water swirling down a plughole. A master editor has ruled out any other possible selection of images to encapsulate the world. Our subconscious would be under pressure to generate a better 4am nightmare sequence. This is sinister perfection. Someone is going to die before our eyes, and we are loving it.

Our hearts beat faster, our breathing becomes uneven. We suppress a scream and watch a naked, vulnerable girl under a showerhead, knowing that behind the saturated white curtain stalks a predator. We are powerless to protect her and watch with a paralyzed horror as the crime unfolds. Clear water suddenly becomes clouded with blood. We shudder, wrecked from sharing the ordeal and sink back in comfortable cinema seats and recover. However, this is only a movie, evil has prevailed for now, but it will lose in the end. The sinister always lose in the end. That is how fairy tales work, especially ones from an earlier time, where the penalty for innocence was death. There were no Disney endings in the 18th and 19th centuries. As for the baddies, there was no redemption for them; these sinister forces almost always died in the end and imaginatively at that.

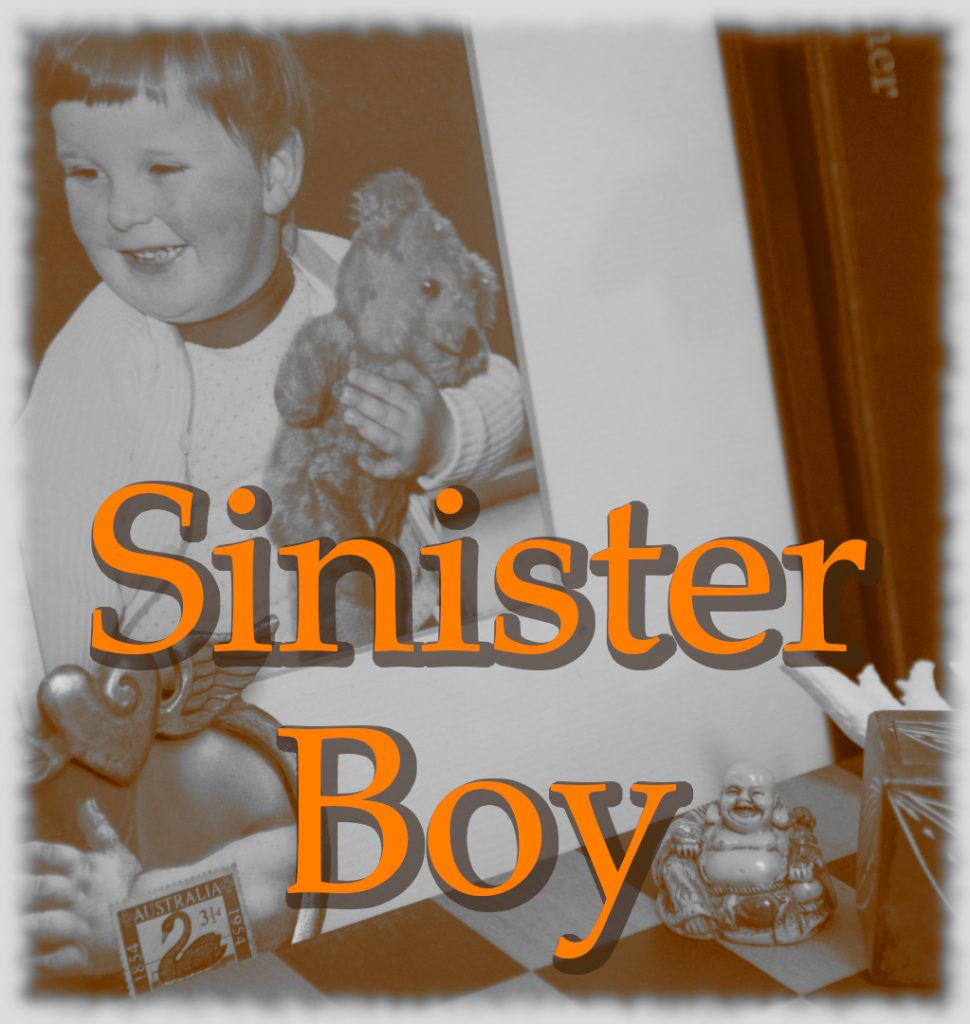

So, how come I’m sinister? Why does this word accompany me through life? How could a toddler, holding a teddy bear, have been deemed a threat to society? How could he be equated with the monstrous manager from the Bate’s Motel in the eyes of religious and civic dignitaries? How was he a threat to anybody; right up there with communists, intellectuals, and left leaning people everywhere? He had one hand. That’s how. He was a ciotógach, a left-handed person, born that way; without even a right hand to mask his true nature.

Like so much in the west, history informs our present prejudice. Going back to a time when we were sun worshipers, there was a marked distrust of left-handed people. Though why worshiping the sun from a right-handed angle should be any different to worshiping it from a left-handed one, is beyond me. Let’s put it down to the, as yet, unidentified Bureaucratic Gene which predisposes us to standardize everything from banana straightness, to points of view.

Populist movements, strange to say, because they disavow them so much, fall into this bureaucratic thinking camp. Afterall, they invariably talk about ‘Them.’ The ‘Them,’ who are not us. The ‘Them,’ who belong on lists, can be singled out, called names, mistrusted, and feared, because they offend the filing system of the Many.

The Romans also put left-handed people on their ‘mistrust’ lists. It is no surprise, therefore, that they gave us the word we still use to describe evil of the worst kind. And that word is Sinister, which is, simply, the Latin word for left.

In Roman regiments of yore, I can understand how left-handed soldiers could ruin symmetry in the ranks if they chose to carry spears in whatever hand suited them best. But where is the harm in it? It is not as though their deaths would be any less heroic than their right-handed comrades.

However, armies love their symmetry almost as much as a good parade. They have a pathological hatred of disorder – that lack of neatness which best defines the human condition. And what illustrates this disorder better than people killing an opponent while carrying their weapon in the incorrect hand. It, simply, is not cricket.

The Roman Catholic Church accepted many of the thinking hand-me-downs of the Roman Empire. But still, what kind of Medieval philosopher, I wonder, refused to investigate their natural prejudice by dismissing, as suspect, between two and ten percent of the population, simply because they used the incorrect hand while making the sign of the cross? In fact, many built upon the theme and saw evil where their predecessors merely saw disordered wilfulness. Maybe a Trumpian thinker was involved, an us-and-them-er, a man who sought power through derision and division; that old Tudor policy of ‘divide and conquer,’ but long before those monarchs came to power.

I wonder what was it about a left-handed copyist which drove these theologians to hate them so? Maybe their quill feathers got up their noses when they popped their heads over the wrong shoulder to check the scribes progress on some Latin text or other he was transcribing. But how did writing with the left hand put you in the Satan camp? Is it truly evil to blow your nose with your left hand? Is unblocking your nostrils with the wrong hand particularly sinful, or maybe just a tiny bit?

It’s not as though this small minority gain any advantage in their daily life from being left dominant. If anything, left-handers are at a disadvantage in very many ways, from flipping burgers in McDonald’s, to playing golf the wrong way round.

But fitting in is only a minor issue for us left-handers. From the very start of my life, this ciotógach struggled with the layout of his environment. He found the world was designed around right-handers. Many kettles, for instance, are right-handed. Right-handers will find that difficult to believe. However, to understand what I am saying you must simply peer through its window, into the very soul of the machine. This can only be done one way. Which means the kettle’s handle is always on the right-hand side. So, lefties must fill it up facing them, then swivel it around before hitting the on switch.

There are many challenges like this one, faced every day by a ciotógach, and I took them all on as a child and tamed every right-handed challenge I met along the way, sometimes easily, sometimes with tears of frustration running down my face.

It did not help that my toolkit consisted of a hammer with a wobbly head, a vice grip with a damaged grip, and a flat-head screwdriver missing half its blade. In ways this was an ideal toolkit for a child. It forced me to sit and stare at the job ahead of me. With such a limited arsenal it was best to figure out how to achieve any task before beginning it. I knew, from experience, that there was nothing worse than pulling something apart and not being able to reassemble it.

Seemingly, it is recognised that left-handers are more creative than their other-handed friends because they face a backwords world every day and conquer its challenges. If this is the case, I must be doubly creative, because not only are most things designed for right-handers, but there is also an assumption of a second hand to aid and abet its companion. My hand has no such compatriot.

For me, there never was a choice when it came to which hand I would write with. And although I had a single-minded left-to-right-hand-conversion-unit, in the form of a sadistic, right-handed teacher, there was little he could do when faced with the options I presented. Mind you, there was about the eyes a look which suggested that I was one-armed by choice and, that given time, he could extract a full confession to confirm his worst suspicions.

Despite his looks of disapproval, I wrote and not like most lefties, who curve their arms over the page and drag the pen behind the hand. I did what many do, I pushed the pen across the page. It meant not seeing what I had just written and, of course, my hand became a smudging tool for drying ink, a sort of non-absorbent blotting pad. The results were more an artistic interpretation of the spirit of writing than true calligraphy. Unfortunately, my teacher was born without an artistic soul and his rebukes were unending. But what the hell, I was writing, or so it seemed to me. It was unimportant that I was the only one who could decipher the text.

My sadist friend had another brief, outside the torture of little boys who were learning to write, one which interested the Huckleberry Finn soul in my ten-year-old body. There were vacancies on the Altar boy front. As this blessed group of students often skipped class to carry out its official duties, I was curiously attracted to the job. Free classes were a dreamed of bonus for a lad whose eyes spent more time roaming the blue skies outside than the contents of the blackboard.

Besides ringing bells, I had no idea what altar boys did, outside of escaping the occasional Irish class. Whatever it was, was ok by me. So, I tentatively enquired about these positions. However, this was when things became truly sinister. There was a right way and a wrong way to make the sign of the cross, it seemed, and mine, I was told, was the wrong way. Then it was suggested that a one-hander could never be trusted with the sacred host. What if the sanctified bread was dropped to the floor? Think of the instant damnation that would bring to my soul, not to mention the shame it would bring to my parents. I’m not sure that there was not even a suggestion that I could not be trusted with the altar wine, even in its pre-transubstantiated state. Enough said, I bore the mark of Satan and would suffer extra Irish lessons because of it. Or so it seemed to me. So, while my alter ego, Huck, and I listened to talk of the heroes of 1916, my right-handed peers were excused classes and scurried off for some spiritually enhancing free time. It occurs to me that they missed out on the great takeaway from talk of the rising, one which Huck and I readily agreed on. The heroes of 1916 would have been better served taking a crash course in military strategies, than studying how to write bad Irish poetry.